Importance of Indigenous Tribal Folklore

Most Himalayan ethnic communities come from strong, spiritual oral traditions. Oral traditions are verbal narratives that could consist of spiritual messages, mythology, and folklore. In the Himalayan region, where there is an abundance of language but the unavailability of mutually intelligible scripts, folklore is transferred to the next generation through stories and legends. It can also be in the form of songs and conveyed ceremonially at appropriate settings. In the original telling of the stories, elders highlighted the symbiotic relationships between humans and the rest of the natural world.

Folklore could include poetry, riddles, songs, music, dances, and also traditional wisdom based on plant varieties grown by farmers, and plant extracts developed by local medicine men. In the Himalayan community, much of the folklore is based on various stories that have been passed down from one generation to another. These stories contain moral values but also the history of the community and how they branched off to settle in one place and how they connect with other tribes in the region. Obviously, many such stories have been influenced by Hindu or Buddhist stories, plots, and characters. But where there seems to be no influence at all, these stories incorporate the idea of closeness between man and nature.

How important are these folklores in an age when children are no longer told these stories and two generations have entirely grown up on Enid Blyton and Fairy Tales? There’s nothing wrong with fairy tales but indigenous folklores aren’t just stories of incredible imagination, plots, and characters. They are about world views, perspectives, philosophies, and morals. Many of these stories, legends, and myths express a responsibility to maintain harmonious relations with nature because all of it is considered to be alive and that the abundance of nature must always be shared equally. Most of these stories are also stories of creation but the beauty of indigenous tribal folklore is that such mythology is rarely enforced upon others. Nor are these stories and mythology regarded as the ultimate truth.

These stories of philosophy about man and nature which start at the beginning of time continue through the telling of cultural tales and songs. No one knows when these stories began. The Khambu Rai people’s Sumnima Paruhang or the Tamang stories of Mhendomaya and Gole Bonbo, inform about the essential philosophy of symmetry, balance, and harmony which are quietly suggested through the adventures of these characters. These stories, therefore, seem to have come from places that have given rise to a symbiotic relationship between man and nature, between genders, thereby creating a circular, ongoing world. Folklore is at the core of Himalayan indigenous culture. It is nothing short of an oral history that explains and records vital aspects of a community. These comprise stories of creation stressing on principles and moral values of the tribes. These are also a part of the Shaman’s songs performed during worship rituals.

Perpetuating history or a belief system through a medium such as oral tradition often leaves room for interpretation for the teller of that story and the listener. Many folk stories of indigenous Himalayan communities also help in not just the understanding of cultural identity but also display the richness of their languages. The narratives within these stories use diverse vocabulary and descriptions which are articulate and expressive. Given linguistic differences, cultural and traditional contexts and nuances, and the transfer from cognition to language, it is important that these stories be read and heard in the native language.

Indigenous folklore must be preserved. The accumulation of wisdom that has been passed down for thousands of years is a treasure trove that can help understand humanity’s past. It could help us find ways to protect and preserve our natural habitats and resources. Such wisdom must be assembled, organized, digitized, and archived but also the traditions of transferring folklore from one generation to another must continue. Individuals and ethnic organizations must identify and help preserve these systems. Folklores reflect the essence of a community’s cultural attributes as a mirror and provide a basis for its cultural and social identity. It is time that communities become protective of this valuable heritage and find a way to preserve their precious folklores that have enlightened countless generations throughout history.

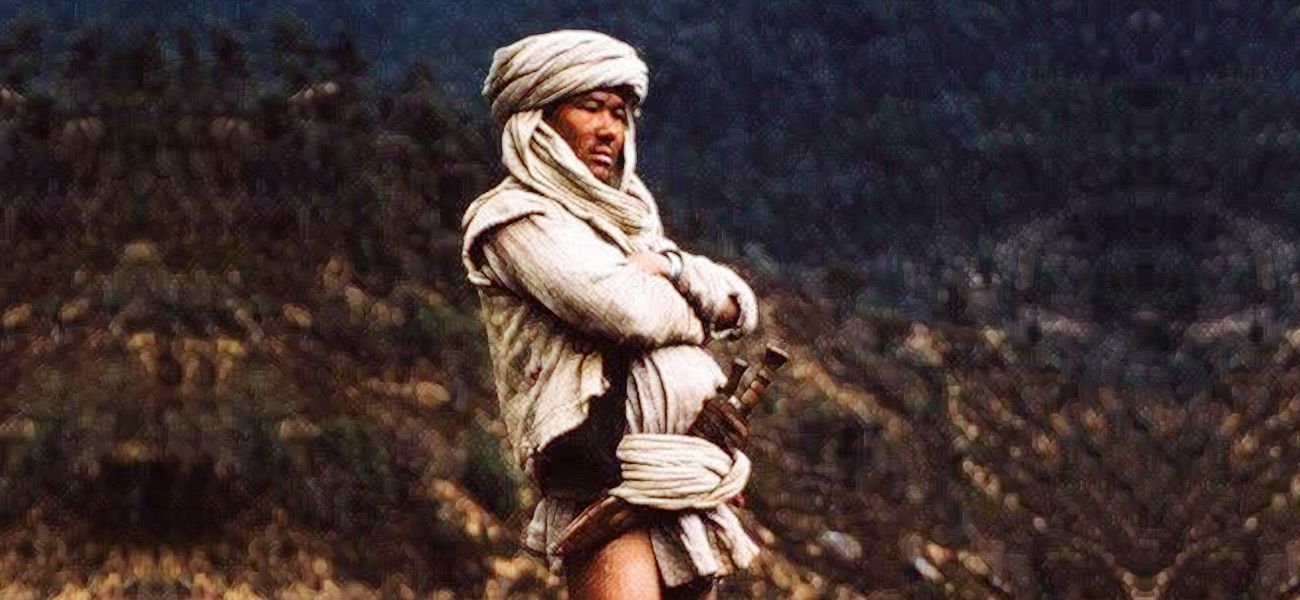

The following video is a Magar folktale narrated by Maya Maski Rana in the Western Magar Language.

Translated and Transcribed by Marie-Caroline Pons

Source: linguistgeek.wixsite.com/themagarlanguage