Much is said of the Newar Gubhaju in the oral sphere, where his name appears sporadically in Newar folklore and in incidental recollections of community elders. In spite of this narrative, there is little sustained scholarship devoted specifically to the Gubhaju. The available material is scattered across short ethnographic observations and fragments of ritual description. Even so, these accounts reveal a practitioner who stands at the center of Newar religious synthesis. The Gubhaju, positioned within the Bajracharya tradition, operates through a repertoire that draws simultaneously from Hinduism, Buddhism, Tantric, and Shamanic practice. This convergence is not incidental to his identity. It is one of the clearest examples of how Newar ritual life brings multiple traditions into a single working system, and it demonstrates a form of religious integration that is rarely encountered in such a comprehensive and coherent expression.

The etymology of the term Gubhaju is unclear. In classical Nepalbhasa (Newari) the term bhaju refers to a respected elder, but the origin of the initial element gu is more difficult to establish. A long-standing explanation links it to the Sanskrit guru, although this connection is not convincing. The title of Gubhaju belongs to an indigenous ritual setting, and it is difficult to account for why a Sanskrit term would be abbreviated and absorbed into a role that developed within Newar religious practice.

A more credible interpretation links gu (गुँ), pronounced with a nasal sound, to the meaning of forest, which appears related to the older Kirata root gum. This interpretation is supported by local traditions in Sankhu, around the Vajrayogini temple area. This was historically known as Gum Bahal, a vihara or sacred Buddhist temple, a site confirmed sacred in Lichhavi inscriptions. The title Gubhaju, therefore, could mean practitioners whose mastery of esoteric mantras and tantric practices were refined within this sacred space.

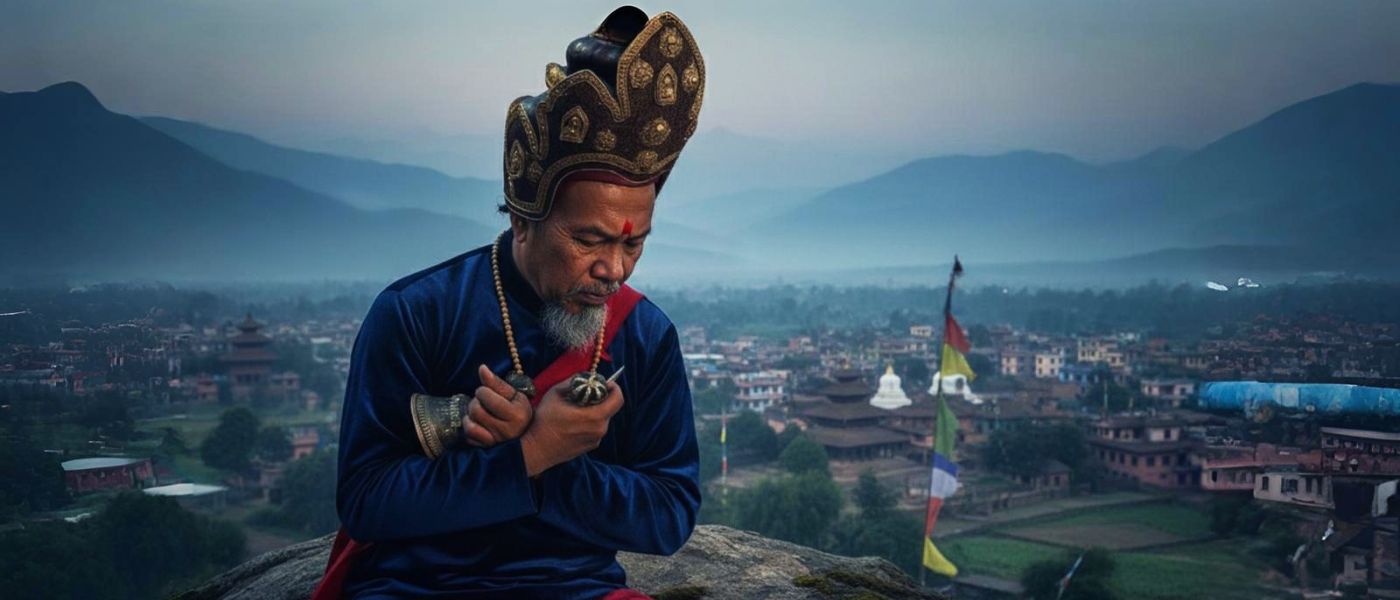

In the Kathmandu valley today, the Gubhaju holds a distinctive position within the Buddhist domain and the wider ritual life of Newar communities. He is often identified as a Buddhist household priest though his work extends into domains that carry deeper ritual weight. His function includes tantric liturgy, spirit mediation, and a range of curative rites that address affliction and misfortune.

Gubhaju belongs to the Newar Bajracharya or Sakya lineages. These lineages form the bare ‘initiated householder monk’ stratum of Newar Buddhism, a group of ritual specialists who maintain family life while fulfilling priestly responsibilities and who remain distinct from celibate bhikṣu orascetic. The Gubhaju’s initiation ceremony, also known as acha lhuyegu, is a moment of symbolic renunciation and return. This temporary ordination grants ritual authority without the establishment of a permanent monastic vocation.

Within the broader social landscape of the Kathmandu Valley, the Gubhaju occupies a dual position. He is both household priest and mantra specialist. His ritual expertise draws patrons from Buddhist, Hindu, and animist Newar communities alike, which other than the longstanding pattern of religious convergence, also reflects collective Newar cultural identity. Although he remains somewhat peripheral to everyday temple routines and public religious discourse, the Gubhaju remains an important figure is the Newar collective memory as a respected elder and a figure whose presence is augmented through legend, rites, spiritual power, and the moral imagination of the community.

Oral traditions portray him as a master of potent spells capable of summoning rain and immobilizing spirits. His exhibits the power to heal all ailments, and sometimes even bring the dead back to life. In a well-known folk tale, the legendary Jamana Gubhaju subdues a malevolent spirit by commanding it to grind rice until dawn, a task that renders the entity harmless and protects the entire village.

Such narratives preserve emic categories of spiritual mastery, siddha gu, ‘to have attained power’ and demonstrate how charisma, ritual skill, and moral authority converge in the Newar imagination. The story recounts how the Gubhaju attained this mastery:

In the old days, Jaman Gubhaju was in a quest for deeper knowledge when no lineage teacher would reveal the practices he sought. This search led him to the Pode settlement on the city’s edge, near ponds and cremation grounds. There he met an elderly Pode known for managing unseen forces. The old man agreed to teach him, writing mantras on belpatri leaves and instructing him to practice beside a pond, for true mastery required facing the beings that move through such liminal spaces.

The Pode told him the mantras would only gain power once he obtained Mohani, a “black shoot” used by dakinis. Gubhaju was instructed to wait at the Balkumari shrine on the fourteenth night of the dark fortnight. At midnight he hid and watched the dakinis dance around three skulls and a pot of Mohani. At the right moment he seized the pot and fled. The dakinis chased him, but his mother barred the door with an iron chain, which repelled them. They demanded the pot, and Gubhaju returned a small portion, keeping the rest as instructed.

At dawn he applied the Mohani to his forehead and recited the mantras. The legend says this moment granted him siddhi and gave him the power to heal, to see spirits, and to confront forces that disturb the living.

A Gubhaju’s ritual duties extend across the life-cycle ceremonies of the Newar life. From Machaabu byankeyu (birth ritual), Bhusaa Khaayegu (first hair cutting), Ihi (marrige to a bel fruit) or Bara Tayegu (marrige to the Sun), Ghasu (death purification rite), a Gubhaju is the preferred officiant for all such ceremonies. Beyond these foundational responsibilities, he performs pitha puja for mother goddesses, bhuta shanti for spirit appeasement, and la gukegu for the retrieval of a lost life force. This ritual variety reveals a continuous harmony between Buddhist liturgy and animistic healing traditions. When misfortune or illness arises, he diagnoses the disturbance through divination that interprets the behavior of rice grains, oil, or a lamp flame. The subsequent rites involve aagwanegu for the welcoming of deities, bhujinigu for feeding spirits, and naasaaḥ paayegu for the removal of malevolent forces. His mantras, often drawn from the Saptavidhi and Kriyaasaṃgraha, are recited in a melody while ringing the ghaṇṭa and wielding the vajra. These are instruments that symbolize ritual authority and the union of wisdom and method.

Healing rites occupy a central place in his repertoire, especially soul retrieval, in which the Gubhaju locates the displaced spirit through divination and then invokes protective deities (dya) while visualizing a mandala that provides the symbolic ground for reclaiming the life force. The restored soul is reintegrated into the afflicted person through sacred water, incense smoke, or chants, accompanied by the pulse of the bell (ghaṇṭa) and the stabilizing presence of the thunderbolt weapon (vajra), all of which support the subtle trance state that validates the efficacy of the rite.

Taken together, these practices reveal the Gubhaju, other than being a ritual performer, is an embodiment of a synthesis of Vajrayana Buddhism and indigenous traditions. His work sustains household and community stability while combining priestly duties with shamanic mediation. His use of chants, ritual tools, esoteric knowledge, and divination displays specialized knowledge transmitted through lineages, and his cross-sectarian engagement highlights a practice-based understanding of religious efficacy.

Although he performs functions similar to a Shaman (Jhankri), the Gubhaju operates within the moral and textual discipline of Vajrayana though his authority is grounded in lineage and scripture. In doing so, he moves between the institutional and the ecstatic, which may resemble shamanic practices but remains distinctive in its own right.

His healing practice is based on the fusion of sacred sound and sanctified substances. The ritual ground is marked as a mandala with colored powders that symbolize a cosmological boundary. Through mantra, the Gubhaju channelizes the presence of deities such as Vajrapaṇi Dyah, Lokeshvara, and mother goddesses like Ajima, to heal the afflicted. When confronting hostile forces, he may conduct nasaḥ payegu, a rite of expulsion in which the spirit is symbolically confined within a pot (ghata bandhan). These rites form the vajra-kriya, a tantric act that unites spiritual potency with practical healing.

For Newars, this work is neither “magic” nor “religion” but dyaḥgu or divine activity. This comes to be a category that dissolves analytic boundaries between ritual, medicine, and sorcery.

Even within a Buddhist framework, the Gubhaju’s ritual behavior displays clear shamanic resonances. Like the Nakchhongs of the Kirati or the Pachyu of the Gurung, he mediates between deities, spirits, and humans, negotiating with unseen beings (nhaḥ lhu gu) to retrieve la (life-force) lost through shock, illness, or ritual transgression. During healing rites, he may enter a light trance known as dyah michaḥ yāyeku (when the deity descends), in which divine presence briefly occupies his voice. His chant becomes a rhythmic dialogue across human and spirit realms. The Gubhaju are also called for the expulsion of wandering spirits or the affliction of malevolent witches (Bokshi), thereby bringing him closer to the category of Shamans.

Gubhajus are often called upon to remove wandering spirits or to counteract the harmful influence of malevolent witches, situating them within a category of ritual specialists comparable to shamans. Their performances follow a carefully structured system that integrates sound and incantations. The ringing of the ritual bell with a measured recitation of sacred words along with the deliberate circulation within the ceremonial space together generate a powerful sensory environment that engages both human participants and unseen spiritual forces.

From an anthropological perspective, these rites enact a form of cosmic realignment, though for the community they are understood more concretely as the restoration of vital life‑energy and communal harmony.

Modernity has reshaped the social position of the Gubhaju. In Kathmandu, many younger Bajracharyas now pursue secular professions, leaving ritual work largely to senior specialists. The spread of biomedical explanations and the rise of reformist Buddhism have further reduced the space for tantrik karmakaṇḍa (Esoteric practices). However, during major festivals and religious events, the Gubhaju remains indispensable for purification and the installation of deities (dyah-micha). In smaller towns and among rural Newars of Kirtipur, Thecho, and Thimi in Kathmandu, Gubhajus continue to perform most rituals and remain influential in Newar social life. Their ongoing presence displays the adaptive resilience of Newar ritual specialists, who reinterpret older practices within contemporary frames of meaning.

As a priest, the Gubhaju exemplifies the continuity of institutional religious practice and as a ritual specialist, he channels ecstatic mediation between the human and spirit worlds. His ceremonies and stories reveal a worldview in which spiritual imbalance and cosmic disorder are addressed through personified performance rather than written doctrine. Even as modernity diminishes his everyday presence, the Gubhaju remains significant through legend and selective revival, and continues to bridge the realms of the sacred and the social. He demonstrates that the spiritual life of the community is not confined to texts or temples but through the skill of those who perform ritual.

Leave a Reply