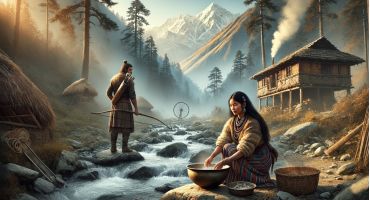

In the beginning, when the world was still new and the sky was close to the earth, there lived a woman named Tigenjungna. She was not an ordinary woman. She had no husband, no people, and no village. Created by the divine will of Tagera Ningmaphuwa, the supreme creator, her presence was part of the cosmic balance, and her body carried the mystery of life.

In time, Tigenjungna gave birth to twins, though no man had ever touched her. The divine had planted life in her womb. One child was born a tiger, fierce and wild. He was named Kesami. The other was born a human, alert and wise. He was called Namsami.

They came from the same womb, drank the same milk, and slept beneath the same sky. Yet one belonged to the forest, and the other to the fire. Both had vastly different personalities.

In the early days, they were never apart. Whether resting in the shadows or wandering through the wilderness, the tiger and the man-child shared their world with no quarrel. But time ripens all things. As they grew, their paths began to split.

Namsami learned to hunt with a slingshot. He chased birds, climbed trees, and made fires. Kesami hunted frogs, beetles, lizards, and later, larger beasts. His eyes gleamed in the dark, and his silence was heavy.

One evening, Namsami spoke softly, “Brother, why do you eat such creatures? There are other ways. We can hunt together, and eat clean food.”

But Kesami growled in reply, “Not only will I eat them. One day, I’ll eat you.”

From that moment, they were no longer just brothers. They became hunter and hunted.

Namsami fled, wandering deeper into the forests, always hiding, never sleeping soundly. All he wanted to do was survive. And behind him, Kesami stalked, his hunger growing. He no longer saw his twin. He saw meat.

Tigenjungna, the mother of both, wept in silence. Her body had birthed them both, and yet, they now walked different worlds. She hid Namsami when she could. He hid him in ravines, on ridges, beneath thick leaves. Whenever Kesami came roaring, she deceived him.

“He’s up in the high hills,” she’d say. “He’s down by the stream,” she’d whisper.

But lies wear down even the strongest tongue. One day, Kesami turned on his own mother, his jaws dripping.

“You’ve lied to me long enough. Tell me where he is or I’ll tear you apart.”

That night, Tigenjungna called Namsami and said, “I cannot lie anymore. My mouth is dry, and my heart is cracking. Listen, my son, go to the ravine. Take your bow and arrows. Climb the tallest Simal (Silk cotton) tree. Hide on the ninth branch. If your brother comes, I will send him there. If I do not, he will devour me.”

Before he left, she planted two flowers in front of her dwelling, upon two dried bottle gourds. Babari (Wild Basil), for Kesami, and Sillari (Cow Parsley), for Namsami. And she prayed, “If the Babari wilts, I will know the tiger is dead. If the Sillari fades, I will know the human is gone.” Then she sat before the flowers, spinning thread and whispering wind-prayers.

Down in the ravine, Namsami waited. The sun passed, the shadows deepened, and then came the sound of leaves rustling. Kesami had found him.

The tiger looked up at the tree and snarled. “So here you are. No more hiding today.”

He began to climb, his claws scratching the bark.

At home, the Sillari flower bent, its petals heavy. Tigenjungna wept, her hands frozen in mid-spin.

Namsami aimed his arrows. Once, missed. Twice, missed. Three, four, missed again. Only one arrow remained. Kesami was almost at the top.

Namsami whispered, “Brother, I begged you to live in peace. But you chose the path of hunger. If you must eat me, don’t make me suffer. Close your eyes, open your mouth. I will jump in myself.”

The tiger paused. Then, with a satisfied grunt, he closed his glowing eyes and opened his jaws wide.

Namsami did not jump. He drew the last arrow, took aim, and released it. The arrow flew into Kesami’s mouth and pierced straight through, exiting from beneath his tail. With a great roar, Kesami fell, breaking branches as he crashed to the earth.

At home, the Babari flower shriveled. Tigenjungna knew. Still, Namsami waited in the tree. He saw flies buzzing over the body. One green fly entered Kesami’s mouth and came out the other end, passing under Namsami’s nose with a stench of death. Only then did he descend. He stood before his brother’s lifeless body. His eyes brimmed with tears.

“We came from the same place,” he whispered. “But your path was your own.”

He took the tiger’s hide and shaped it into a drum, the Chyabrung. With each beat, it roared like Kesami had once roared. It was not made for celebration. It was made for remembrance.

Today, the Limbu Chyabrung drum still echoes through the mountains, through the homes of the Limbu people. When the Chyabrung speaks, it tells the tale of the first tiger and the first man, born from the same mother, children of nature, fated to walk separate paths.